ah … I think, I don’t think it will be a problem (laughs) … to answer all the questions …”

During the interview, Sasha – twenty-one years old but looks like a teenager – is nervous. He stumbles over his words, starts over. When he starts to recount a story, his eyes light up, his expression sobering again at times as he concentrates on remembering something. He smiles often – in this new situation, with the inquisitive young researcher facing him, it is partly about building mutual trust.

When the interview in Novosibirsk took place, in September 2017, Sasha had only been an activist for a few months, during which he worked on the 2018 presidential election campaign of opposition politician Alexei Navalny . He is one of 23 interview subjectsin a research project carried out in seven big cities in the autumn of 2017. The semi-structured interviews were intended to seek out the respondents’ personal motivations and political convictions, but also to elicit details about the activists’ experiences in Navalny’s campaign. Sasha is just one example of the many people for whom the campaign was the first introduction to political activism.

asha says in the interview that he “was somehow always interested in politics” but had never been actively involved himself until March of 2017, when he came across a video posted by Navalny accusing Russian Prime Minister Dimitry Medvedev of corruption. The video had gone viral, getting more than 10 million views in just a few weeks (over 31 million to date).

“I saw the movie, and well it like really struck a chord with me. I already knew that there’s well, you know, corruption in Russia and all this other bad stuff, but somehow it really made me do it, this movie, it made me start some kind of active engagement”

When a demonstration was held in Novosibirsk under the slogan “We demand an answer” on 26 March 2017, Sasha went. Navalny’s campaign has been organising rallies like these in many cities around the country. The aim is to get Prime Minister Medvedev to respond to the allegations of major corruption. Sasha meets other young people at the demonstration who invite him to stop by the campaign office, which has just opened.

“I didn’t really know much about this either. I mean, this kind of active engagement I’m doing as a volunteer started in April. Starting from April I’ve been involved in, well, basically in everything”

And now he is part of this too – right in the middle of it. He knows where to hide the flyers when the police come by to do another unannounced search of the office. He knows the arguments, as when a relative complains that he shouldn’t allow himself to be used in the service of other people��’s political ambitions. And he is now on familiar terms with some of the big names in the local activist scene, the ones who give lectures at the campaign office in Novosibirsk and speeches at the demonstrations.

For Sasha, and for many others, the demonstration on 26 March was an extraordinary experience, one that for now has decisively altered the course of his life. Sociologists like Donatella della Porta or Olivier Filieule , who study the socializing effect of protests, attribute a veritably transformative power to experiences of this kind: they wrench people out of the familiar context of their normal lives and show them new perspectives on themselves and the environment. But protests can also simply cause participants to meet people whom they would otherwise never have ever heard of – as in Sasha’s case.

Alexei Navalny’s campaign made effective use of these social mechanisms: first a viral video, aimed particularly at a young audience. Then a demonstration that delivered these unusual emotional experiences and provided a first taste of collective action. Young people wanting to get involved in a cause could easily identify with the stylish and dynamic campaign. Moreover, because of the campaign’s streamlined, centralized (and authoritarian, according to some) organisation, the new activists did not need to have any prior experience. Further protest events in the regions organized by the campaign (now with the help of many people who had been mobilized for the first time) created a sense of community, one that was fed, to some degree, by the shared experiences of repression and counter-mobilisation from anti-Navalny groups. A wave of young activists emerged.

ssentially, Navalny channelled an existing dissatisfaction into his political project while mobilizing people who take joy in social action and who have been gradually growing into a team. The fact that protest events are deliberately embedded in political campaigns does not mean that the protest itself is not authentic or is unjustified and thus illegitimate, as one often hears pro-government commentators claim.

Moreover, the history of Eastern Europe demonstrates that mass protests that support concrete counter-elites can result in lasting democratic changes. Assuming, that is, that civil society is able to keep these counter-elites in check once they have taken power, which often turns out not to be the case – as the so-called colour revolutions in Georgia or Ukraine often illustrate.

Nonetheless, wouldn’t one have to say that the youth who joined the campaign were, at a minimum, acting recklessly and imprudently? Sasha, for one, mentioned in his interview that he had been accused of being used for “political games”. But this accusation fails to acknowledge that Sasha made his own decision and thereby denies his agency, and the agency of all other activists. There were, after all, good reasons not to become involved: Sasha’s friends, he says, did not find Navalny the least bit convincing at first. That is why he went to the demonstration alone on 26 March – an act associated with some personal risk aside from all else.

Asked about possible repression or personal problems that he might encounter as a result of his activities, he explains:

“Actually I hope there won’t be any problems, but I get it that it could happen. I don’t know what they will look like, but, again, anything can happen”

o what extent was the campaign able to attract the support of “newbies” like Sasha? To what degree did it rely on the work of experienced activists?

A survey of Navalny’s supporters on the social media site and Russian equivalent to Facebook VKontakte provides an answer. One tenth of those who took part reported being actively and regularly involved in the campaign work (by handing out flyers, for instance); of these, a slight majority had never participated in a demonstration before the country-wide protests on 26 March and 12 June 2017 organised by the Navalny campaign. And half of the activists surveyed who said they had taken part in one of those 2017 demonstrations had not had any prior experience with protests at that time:

The figures show that the majority of those active in the campaign (60%) had no previous experience with political activism or activism of any other kind.

It appears that the campaign was successful in recruiting a relatively large group of campaign workers with no prior experience of activism.

But what about experienced activists? The campaign was able to appeal to them as well. This becomes clear when one breaks down the group of activists according to how frequently they engaged in campaign work. The proportion of people with prior experience in political or social activism is higher among groups of particularly active campaign workers.

Thus, although Navalny’s campaign mobilized a lot of new activists, it was not by any means only people like Sasha who kept it going.

rotest can help a political campaign recruit new activists, but that is not its only possible function: a campaign can also use protest to try to score political points. One way it can help is by generating images suggestive of broad support: a figure who can rally people across the country to support his message must enjoy a certain amount of backing. This is why parties and established public actors sometimes try to attach themselves to grassroots protest to promote their own political projects. Activists often explicitly object to this and try to distance themselves from all political forces.

Another thing a political campaign can do is to use an opponent’s repressive reactions against him, to “expose” the opponent or to present a counter-interpretation of the opponent’s behaviour. A good example of this are the tweets by Navalny and his colleagues in which they communicate their own political messages by providing examples of repression or restrictions on campaigning activities:

Alexei Navalny

@navalny

A fully sanctioned protest will take place in Yekaterinburg on 5 May. Despite this , the police are at our offices at this very moment in the process of confiscating our invitations to this sanctioned protest. People of Yekaterinburg, you know what to do . 5 May, 3 p.m., October Square. In front of the Drama Theater.

3 May 2018

398 Retweets | 2.234 Likes

Alexei Navalny

@navalny

“For your freedom and ours” (Protester in an avtozak )

12 June 2017

636 Retweets | 3.188 Likes

Leonid Volkov

@leonidvolkov

“And here we have it, my favorite, my dear article 144, paragraph 3 of the Criminal Code”

(The journalist is holding up his press pass).

12 June 2017

136 Retweets | 478 Likes

Alexei Navalny

@navalny

For a lone protest against the arrival of Ballon the sentence is 10 days in jail. This is how the authorities keep the peace for a filthy liar. When I traveled around the country during the elections, even when paid Putin activists poured zelyonka on me , the police said: No one has broken the law.

12 June 2017

636 Retweets | 3.188 Likes

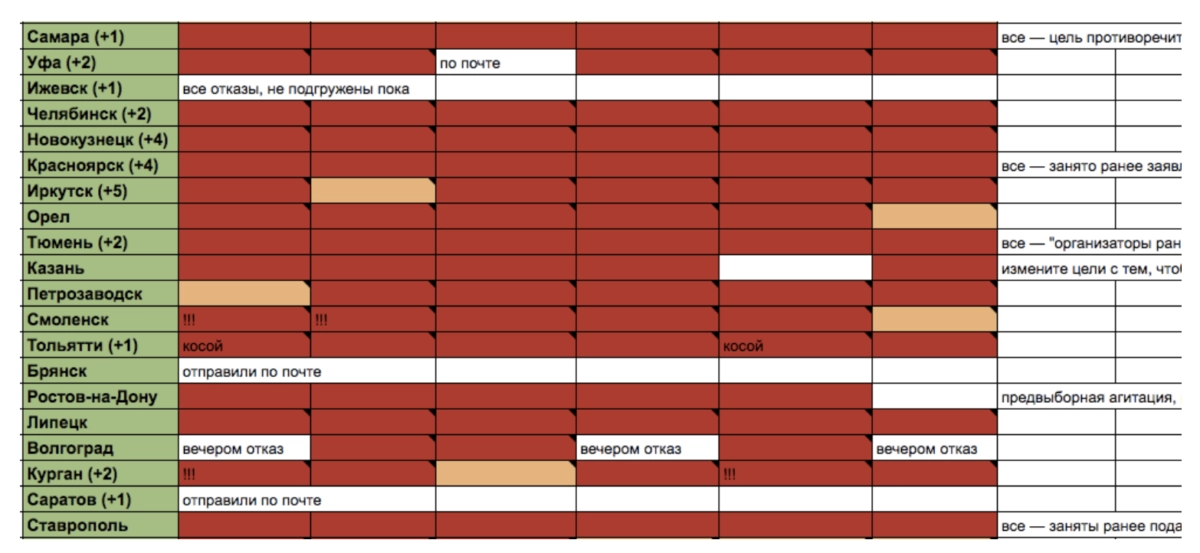

This technique can work even if no demonstration actually takes place: when Navalny was planning a tour through cities all over Russia in the autumn of 2017, his team sent requests to register events in dozens of municipalities in order to fuel the campaign with live appearances.

After an initial round of successfully registered appearances, officials began to refuse the requests – often unlawfully. The campaign’s response was to attempt hold the events on private property, but it also went ahead and published its planning list, which consisted largely of red refusals.

Thus, protest played a key role in the campaign’s depiction (or framing) of its political opponents. The campaign portrayed itself as well organized and law-abiding. Institutions that actually should be politically neutral, however, such as the police or the local authorities, were being used – at least according to the campaign – as tools to maintain the political power of Vladimir Putin and the ruling party by systematically placing obstacles in the path of legitimate challengers.

Though the campaign overstates and oversimplifies this diagnosis, the diagnosis itself is pretty much in line with the findings of research on “hybrid regimes” . This term describes regimes that outwardly have democratic structures and misuse state institutions to curtail the scope for political action by their political challengers.

For instance, candidates and parties are often not excluded from elections on the grounds of “formal errors”, or refusal to register demonstrations on the flimsiest of grounds.

Another factor in Navalny’s case is the unofficial ban on his appearance on state-controlled television. This renders protest and the reactions it provokes in political communication all the more important.

And news of such tactics, as Sasha explained in the interview, has spread all the way to Novosibirsk:

“One of my friends thought, well like, this Alexei Navalny guy, and this whole campaign, like it’s a scam, a fraud and all that, but actually he really changed his mind, I think, with everything that’s happened lately. I mean, for instance I tell him that they arrested Navalny again, and he asks: “Why?” I told him that he called people to come out to the meeting that had been approved. He says: “Well thats just beyond anything”. Like, it’s also starting to worry him.”

asha’s story and Navalny’s campaign clearly illustrate how protest functions as part of a larger political project. On one side, you have, Navalny, who, along with his strategists, is perusing a long-term aim: Navalny wants to replace Putin as president and – or so he says now, at least – make Russia more democratic, strengthen the rule of law and combat the enormous economic inequality in the country.

On the other side there are people who want to work towards political change, whether due to dissatisfaction, because they enjoy being a part of something, or a combination of both. Without these people, their ideas and their enthusiasm, Navalny would probably still be just a lawyer and anti-corruption activist. But it is the campaign’s strategic planning that makes it possible to mobilize this diverse group of people to work for a common goal – to channel their urge to resist.

Thus, Navalny’s campaign is based on the linkage of top-down and grassroots elements. This has not always been the case: the element of spontaneous, not particularly targeted mass protest was predominant in the 2011-13 protest movement and the protests against the exclusion of independent candidates in the summer of 2019. Supporting specific political actors was not particularly at the forefront of these movements, although naturally strategic planning also played a role. Hence, the weight of each of these elements differs from protest to protest. But both are necessary for lasting and successful protest with political goals.

There is also a latent conflict between “top-down” and “bottom-up” though. A case in point: social protests are often supported by the Communist Party, such as the demonstrations against raising the retirement age in 2018. The KPRF contributes funding, organisational capacity and experience (in coping with repression and court proceedings, for example), which is often beneficial for a protest. But, as previously mentioned, activists also sometimes accuse the party of using the protest primarily for its own ends.

These latent or overt tensions between political actors and grassroots movements exist in other countries as well, and in other political environments. They are particularly characteristic for Russian society, however, a society in which political processes have played out largely outside the public eye for a long time and in which genuine political competition is systematically blocked. Political engagement is often seen not as something normal, but as a dirty business intended for personal gain, and yet, at the same time, opposition actors must rely more heavily on public awareness and the mobilisation effect that protest triggers than is the case in more open political systems. Thus, the importance of protest’s political function is particularly evident under these conditions.